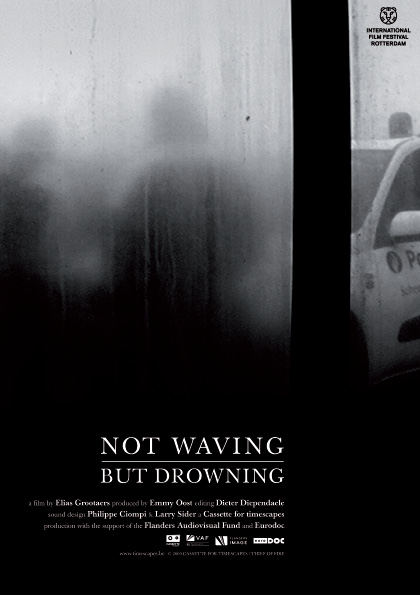

Not Waving, But Drowning depicts the experience of a group of Indian refugees during their arrest and detention by the coast guard in Zeebrugge, Belgium. Within the tense and haunted setting of the harbor and the seaside, we slowly lose all sense of time and place in the group’s company. Without probing into their past or their future, human traffickers or Belgian asylum law, the film transgresses into the timelessness in which our society imprisons undocumented migrants.

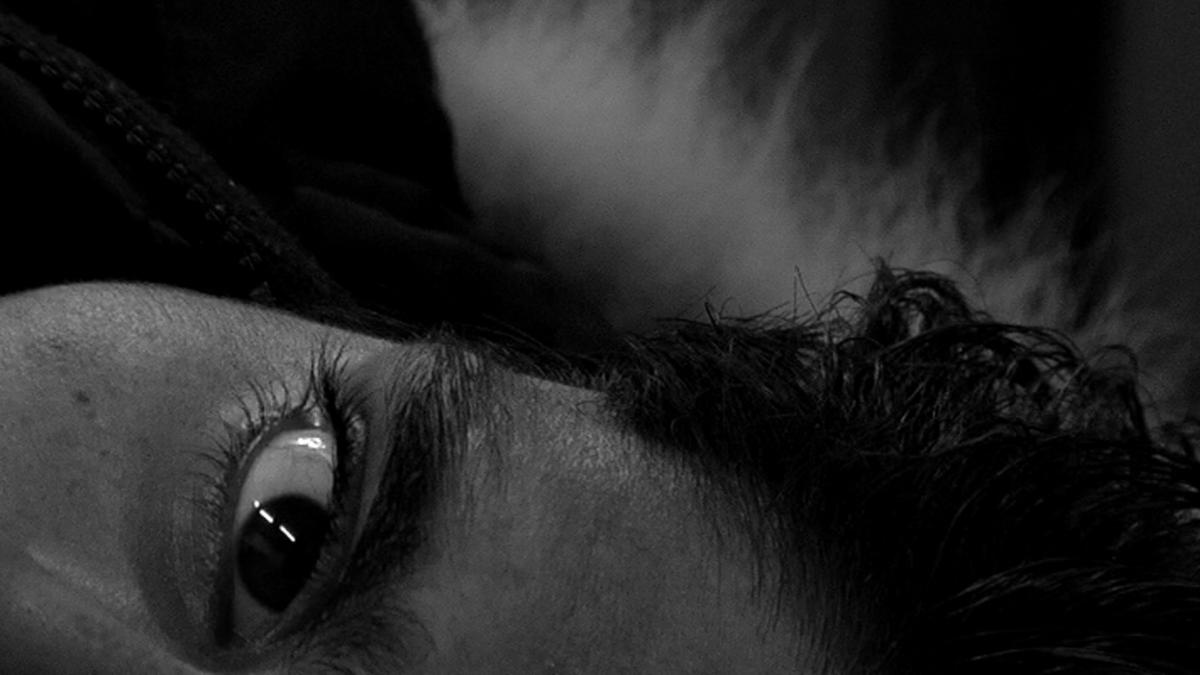

“Not Waving, But Drowning is set in a detention center in the Belgian harbour town of Zeebrugge and documents the waiting time of a group of young Indian migrants who were arrested here on their way to the UK. Left without a translator, they remain uninformed about the nature and length of their detainment. Their bodies are disassociated from all productive activity in this confined space. Their existence revolves solely around fighting boredom and killing time, they are reduced to an immediate immersion in the present moment. They are drowning in a sea of time. There is nothing to do for them but to lie around: to sleep, to eat, to compulsively wash hands, to stare out of the window, to sing mournful songs. […] In order to explore how this temporal regime manifests itself in the migrants’ minds and bodies, Grootaers frequently takes on the detainees’ perspective. His camera stands on their side, follows their views through the glass door to the exterior corridor, and shows us what they can see. Thus, the policemen appear as intruders in the migrants’ space and we feel their disconcertment about the incomprehensible explanations and orders they receive. The images he composes feel constricted and often are framed by doors or barred windows. The sound attains a haptic quality, with the locking and opening of doors producing a visceral feeling on the side of the audience.”

Steffen Köhn

“Alternating between exposure and occlusion, the film’s impressionistic aesthetic style acts in contention with its documentary aspirations to draw audiences’ attention to the realities of forced migration and Europe’s response to the presence of asylum seekers on its borders. Only ever depicting his subjects partially, Grootaers shoots either in extreme close up – an eye, a hand – or through some visual obstacle such as a steamy window or metal grill. While documenting their physical incarceration, these claustrophobic shots also refuse to present the asylum seekers as whole and knowable beings, disrupting the more traditional generic aims of documentary: to bring something to light and expose it to scrutiny. Questioning the ethics of his own act of representation in this way, Grootaers shields the asylum seekers he depicts from the ambiguous gaze of the camera, demonstrating his awareness of the vulnerability of the film’s subjects and the dangers inherent in their exposure. […] Perhaps the prevailing insight afforded by Grootaers’s image, and the film as a whole, is that representations cloud as much as they clarify, and that this tension between occlusion and revelation is most ethically and politically pressing in relation to disenfranchised groups who have only limited access to the means of self-representation.”

Agnes Woolley