On February 26, 2024, Avila and Sabzian presented a unique cinema concert at Bozar. Pianist Seppe Gebruers accompanied Charles Dekeukeleire's avant-garde masterpiece Histoire de détective live on two grand pianos. The recording of this concert is now available online on Avila. Discover how the music interacts with the film's playful absurdity and unexpected rhythms.

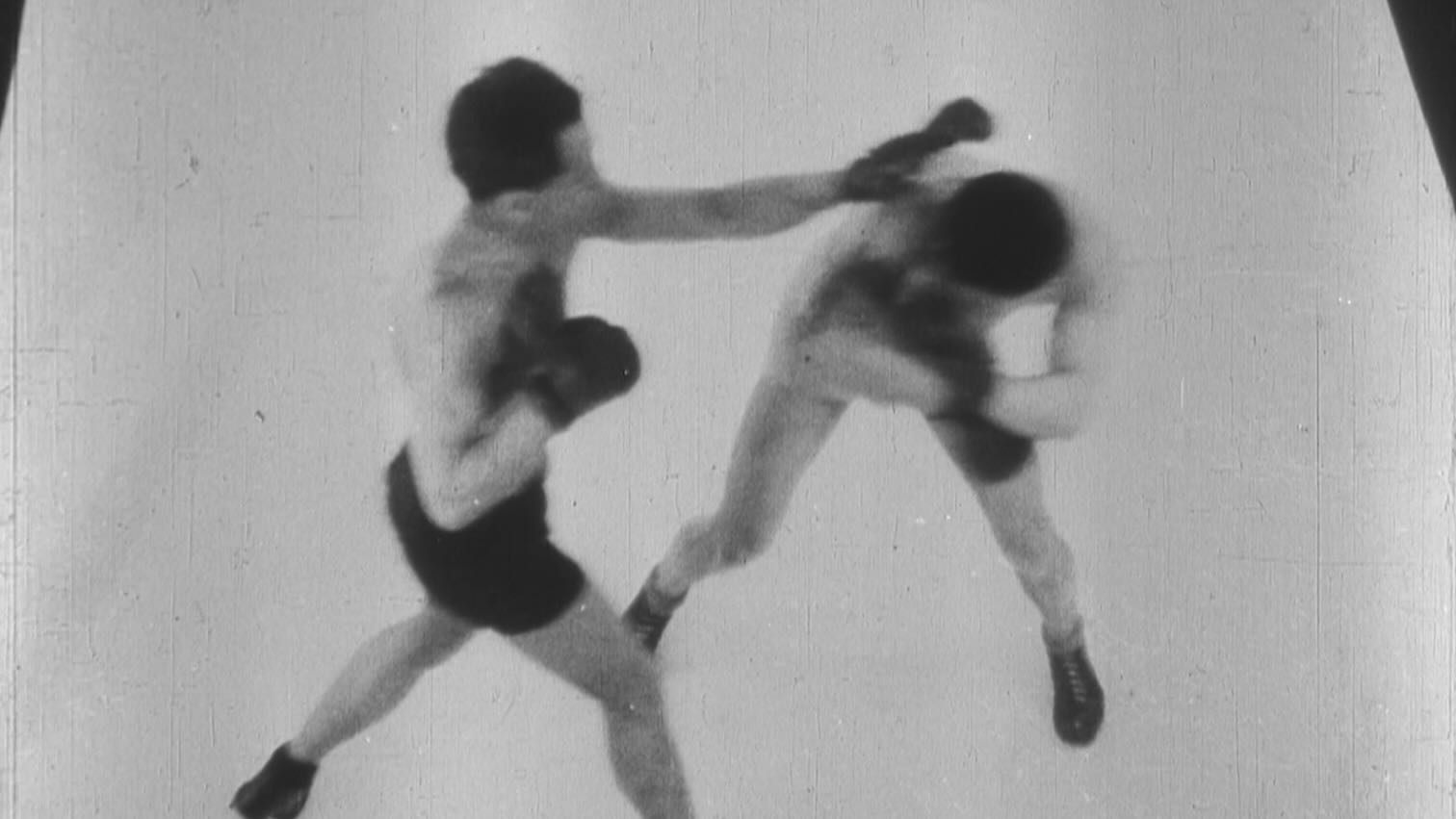

A woman, concerned about the continual absences of her husband, commissions a detective to follow him and report back to her. At first glance this appears to be a classic fictional device, all the more so since Charles Dekeukeleire segments his film with titles informing us of the latest developments of the story. Yet this framework serves only to set up a narrative pretext for disrupting narrative itself in favour of pure cinema. For the detective uses photographic equipment as an instrument of investigation: thus, the camera becomes the principal character and its subjectivity the principal subject of the film.

The melancholy of Monsieur Jonathan and his eventual reunion with his wife rapidly become the least of both our and the director’s worries. The film is preoccupied with something very different: the camera-eye (Dziga Vertov’s film dates from 1928), a voyeuristic instrument which records fragments of the real to organize a reality which would be truth. The investigation thus becomes the history of a film, with the hazards of shooting, its hidden (and hindered) camera style, the editing and projection. The fictional happy ending leaves unresolved the fundamental issue: how does cinema relate to reality? The photography and camerawork exploit the imperfections of the reportage or stake-out, such as focusing errors, double exposures, fragmentary and ambiguous information and the ordening of shots into impressions rather than information. Providing counterpoint and harmony, the titles designed by painter Victor Servranckx similarly play with their narrative function, only to quickly distance themselves from it, preferring pure visual experimentation.

“Histoire de détective is an experimental film which allows narrative in, only to negate it by suppressing, not just acting, but all the visual conventions which the silent cinema had built up to present story material to the spectator.”

Kristin Thompson

“The author’s great merit is his break with a tradition he finds outmoded and his discovery of a new method of expression. I am enthusiastic with regard to certain fragments of this film wherein are mingled the freshness of a sentimental naivety and a rhythmic treatment of the image that expresses the author’s temperament in a vigorous, sane, constructive manner.”

André Cauvin

“This film will be contested because it reverses the normal attitude of the spectator. He may no longer be an indifferent observer, sharing or not sharing the proffered joys and sorrows. He is, as it were, flung violently into the mêlée. His eye is held by the screen and he is left unsupported by the artificial logic that has been established for everyday use and for the purpose of facilitating understanding and establishing pleasure. There are no love-scenes to be observed with the tranquillity of one accustomed to examine detail through opera-glasses. The elements that make for rational thought are sown within the whirlwind of sentiments and disordered ideas. And these images, rising from the subconscious, succeed each other in a disorder that is often much more significant than are the most logically-ordered intellectual processes.”

André Cauvin

The soundtrack was created in the context of Gebruers's research "Playing with ..." at KASK/UGent. This serves as a study of visual orientation as a play rule for musical composition, as well as how the perception of 'movement' can be transformed through the use of quartertones.